Pictured above: Francisco Casas (left), Pedro Lemebel (right).

I first learned about Chilean artist and activist Pedro Lemebel while watching an interview with Chilean queer musician Alex Anwandter about his latest album, Amiga. On that album, there’s a track called Manifiesto in which he tackles themes of gender and sexuality; a track that Anwandter said was inspired by the life and words of Lemebel. After watching the interview, I began to research Pedro Lemebel obsessively and thus began my journey into discovering the magic that was the late, great artist. After reading countless interviews, watching YouTube clips, searching for articles and diving deep into the bowels of the internet, I decided to share a little bit about what I’ve learned in the hopes of introducing Lemebel’s work and legacy to a broader Latinx audience here in the U.S.

Pedro Lemebel

Pedro Lemebel was a queer and gender-bending writer, activist and performance artist heavily involved in Chile’s art and political scenes during the 1980s and until his death in January 2015. In his work, Lemebel often used humor and sarcasm to uplift the experiences of working class people living in the capital city of Santiago.

He particularly elevated the stories and realities of queer and trans folks who lived in poverty, marginalized not only by mainstream society but also at times by leftist circles and leaders active in the city. In September of 1986, during a leftist meeting made up of groups opposed to the Augusto Pinochet dictatorship, Pedro Lemebel staged what he called an “intervention of the left”. Lemebel walked into the meeting with a hammer and sickle painted on his face and wearing high heels (shoes which he often referred to as his weapons and armor), and read aloud a piece titled, Manifiesto (Hablo por Mi Diferencia), in which he exclaimed, “…but don’t speak to me about the proletariat, because to be poor and a faggot is worse. You have to be acid to withstand it.” He goes on to say, “I am not going to change for marxism, which has rejected me so many times. I don’t need to change, I am more subversive than you…” Despite his vocal rejection of the Marxism of his straight counterparts, Lemebel was known as a radical and maintained loyal relationships with leftist leaders such as Gladys Marín and others.

In addition to being politically active, Lemebel was also an avid writer and became well known in the literary world for his crónicas urbanas. In 1995, he published his first book of chronicles titled, La Esquina Es Mi Corazón, followed by many others. In 2001, Lemebel published his first and only full novel Tengo Miedo Torero–a love story between an older drag queen and a young leftist revolutionary who is plotting the assassination of dictator Pinochet. Torero is the only one of Lemebel’s books that has been translated into English, titled My Tender Matador. The protagonist of the novel, “la reina de la esquina” (queen of the corner), is a character that is very much influenced by Lemebel’s own experiences and self-perception. It tells a story of political and sexual desire, of poverty, of revolutionary spirit and most certainly of romance and love–all during a Chile still ruled by dictatorship.

Undoubtedly, Lemebel was a badass, intersectional guerrerx who fought not only for poor, working-class queer and trans people but also for political prisoners, for indigenous Mapuche communities, for women, and for all the people and families terrorized under the Pinochet regime. Lemebel’s legacy is one of queer liberation, feminism, intersectionality, and the greater collective; a legacy of both words and actions. A legacy that is perhaps most evident in the work of an art collective that Lemebel helped form and performed with for 10 years of his life.

Las Yeguas Del Apocalipsis

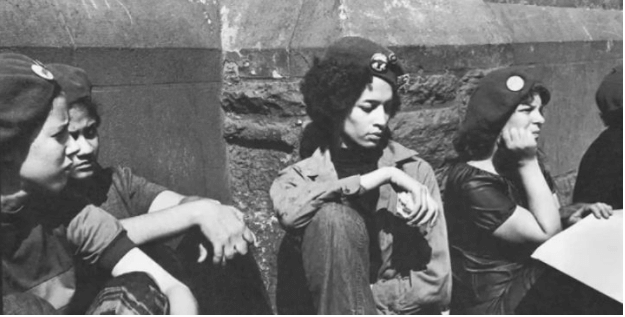

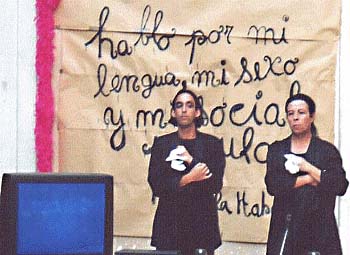

Between 1987 and 1997, Pedro Lemebel and fellow queer artist Francisco Casas performed as the fabulous and deviant art troupe Las Yeguas Del Apocalipsis (The Mares of the Apocalypse). The two artists created the group as a way to combine alternative forms of art and politics and to create space for a radical queer “underground” culture amidsts the more “establishment” aspects of the socio-political arena in Santiago. They engaged in “public intervention” performances that challenged cultural and political narratives and assumptions; from the colonization of Latin America to the dictatorship of Pinochet to the homophobia and transphobia in broader Chilean society.

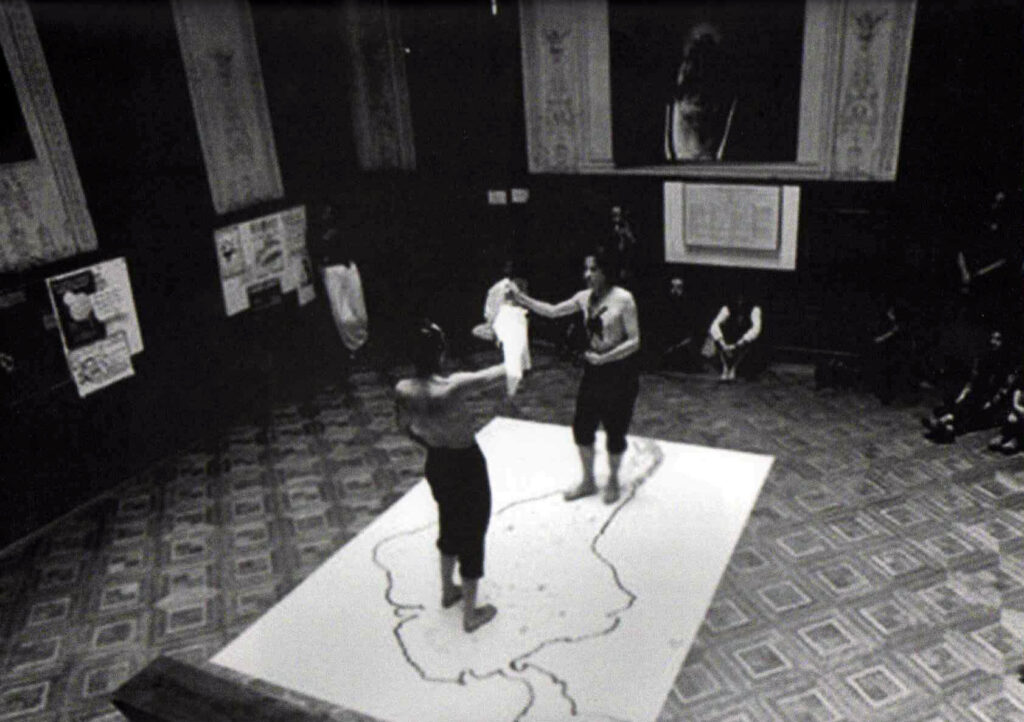

In an article published in The New Yorker, Gary Garthwall describes one of Las Yeguas’ most poignant performances, titled, La conquista de América:

“…the two artists, barefoot and stripped to the waist, with Walkmen taped to their chests, danced the cueca, the national dance of Chile, on top of a white map of Latin America. Bits of glass from broken Coca-Cola bottles were scattered on the floor, and as they danced the map became stained with blood.”

They performed this act at the Chilean Commission on Human Rights in October of 1989 just as Chile was preparing to transition out of the 17 year dictatorship of Pinochet. La Conquista de America represented and connected both the long history of colonization throughout the Americas as well as the more recent history of neoliberalism and dictatorships.

Casas and Lemebel also used their art to speak on the issues that affected working-class and poor LGBTQ communities of Santiago. In a piece called Lo Que Se Llevó La SIDA they tackled the crises of HIV/AIDS. In La Ultima Cena de San Camilo they sought to highlight the lives of trans women who were sex workers and were being pushed out of their neighborhoods and the streets where they worked as a way to “clean up” Santiago as the city prepared to usher in a new era post-dictatorship.

The legacy of Las Yeguas can serve as a reminder that our duty is not only to survive in the face of repression but also to thrive, to unleash our political imaginations and to move us forward into what is possible when we come into la lucha as our whole selves; challenging oppression while also showing to the world and to each other that we as queer latinx folks can hold tremendous beauty, joy, creativity and resilience in our bodies, hearts, and souls.

Discovering this Chilean queer history has been a grounding and healing experience for me. Growing up in the U.S. for 20 years (without going back home until very recently for the first time), I used to wonder what my life would have been like if my family never left. I used to think about what my development as a young queer kid would have been like; how my political education and values would have been shaped. I think deep down I wanted so badly to feel connected to a Chile that also spoke to my queerness and my politics and I didn’t know how to feel that connection or where to begin looking for it. After doing all of this research, I feel like I’ve found that bridge and a part of me feels a little bit more whole as a person.

Cheers to Pedro Lemebel, to Las Yeguas del Apocalipsis and to all of the fabulous queers who resist, who breathe fire and joy into the world and who do it with a flamboyant courage across time and space.

PS: If you’re interested in learning more about Pedro Lemebel, watch this video interview Trazo mi Ciudad — Pedro Lemebel. ¡Ojo! The video is amazing and allows you to hear from Pedro Lemebel directly but it is also in Spanish and has no English subtitles.

PPS: Here’s a rough translation of the poem Manifesto (I speak for my difference) for your reading pleasure in English

Salem Acuña is a queer latinx immigrant originally from Santiago, Chile and currently based in Washington, DC. Follow him at @SalemAcu89