Early this November, Perú burst with uprisings across the country in response to the ever present political instability and violence. What happened in the last month and what can we learn from folks in the front lines? As part of this second iteration of Resistencias Beyond Borders, we spoke to Gahela Cari Contreras (27), a trans indigenous migrant woman activist born in the south of Peru and based in Lima. Gahela is also one of the founders of Nuevo Peru, a left-wing grassroots movement and is running for congress next year with the slogan “For a true TRANS-FORMATION of politics in our country.” If she wins, she will be the first trans indigenous woman elected to congress in Peru.

THE PANORAMA

“Peru, like various parts of America, is a territory that has suffered not two months ago, not four or five years ago,” says Gahela, “but rather, one that carries a struggle or a history of resistance.”

She tells us that within this history there have always been people who have tried to survive despite the limitations of adversity, in the middle of a system that pollutes and murders, that generates inequalities, such as the predation of forests, poisoning of lagoons, increase of the number of children with lead in their blood, the number of femicides and hate crimes that continues to grow, the fact that racism continues to prevail with total impunity, and more.

All these inequalities can be attributed to the fact that the government and politicians are making policies, laws and regulations behind closed doors to suit themselves. Working on extractive projects under the guise of “development,” that ultimately kill natural resources and the people that work on the land. According to Gahela, the context of the pandemic has only exposed the levels of inequality and precariousness and only made visible that “the dream of a successful Peru” did not exist.

“Never was there a country moving towards development. The development was only for a few who have tried to maintain their privileges,” says Gahela. “Every time, the situation has worsened to the point of generating a political, economic, labor, social and environmental crisis that has been impossible to sustain.”

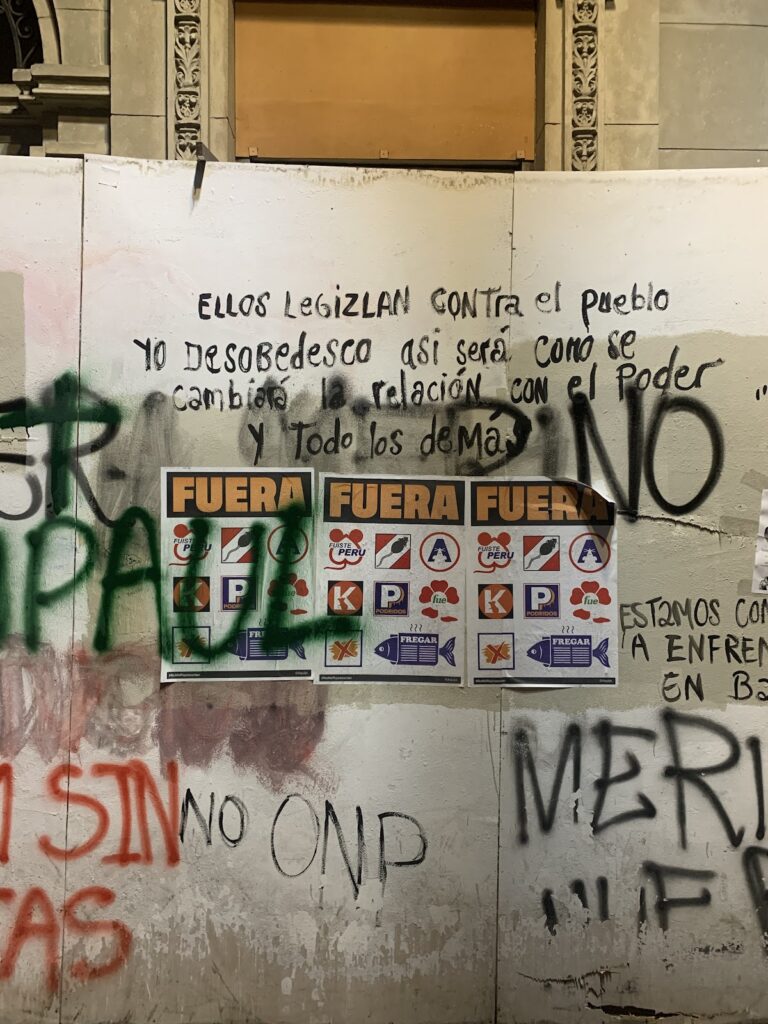

She tells us that what we’ve seen in the past month has been a congress trying to seize the Executive Power and Constitutional Court to have all the power. “All this to on the one hand stay in their positions, but on the other hand also to push laws that are harmful to the population, but beneficial to their pockets.”

This has caused citizens to be outraged and take to the streets, shout for changes, to demand the resignation of Manuel Merino, who was the president of congress turned coup-leader who assumed power thanks to the coup that a group of 105 “murderous, coup-plotter and under-investigation” congressmen carried out on November 9.

“As a result of all these mobilizations, Merino ended up resigning,” shares Gahela. “However, this is nothing more than a small change that will not solve the lives of Black and indigenous people, it will not solve the lives of women, it will not stop gender violence, corruption, inequality, hunger and poverty.”

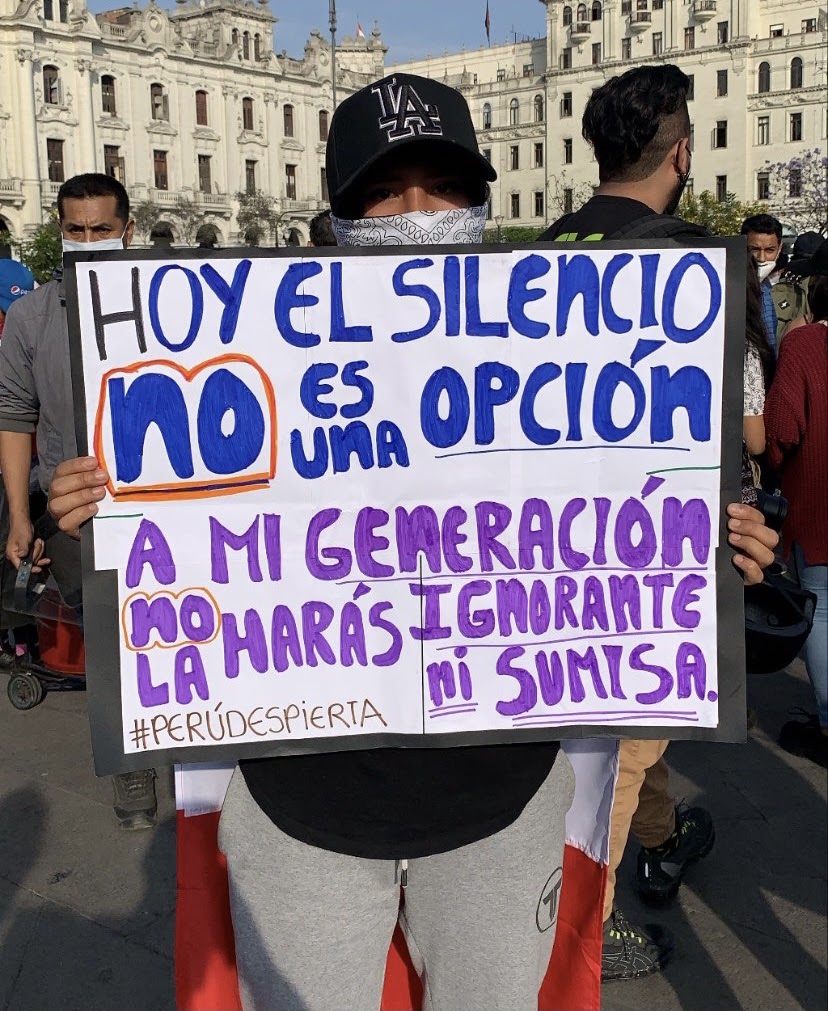

Who has taken the streets? “Almost in its totality it has been young people,” she shares, “a generation that these traditional politicians underestimated.”

LGBTQIA+ PRESENCE IN THE UPRISINGS

Gahela tells us that these protests have been different from all the previous ones because who she has seen most in the streets have been young people and not just heterosexual youth, nor just cisgender youth, but rather, young people in all their sexual and gender diversity.

“I have gone every day of the protests, from very early to very late,” she says. “And amidst the tear gas, amidst the pepper spray, amidst the police abuse, I have seen many young women and many LGTBIA youth, helping in the midst of all that difficult context, giving respite to those who were suffocating, sharing vinegar with water mixed with bicarbonate, assisting those who were ill.”

Gahela remembers approaching Abancay street, the night before Inti and Bryan’s murders and seeing many people suffocating because of the tear gas bombs. “In the middle of all that I saw queer boys, lesbian and trans girls with their bicarbonate mixed with water and their cloths helping people. And it wasn’t the only day I saw this.”

She tells us that there have been several calls from LGTBIA movements for folks representing sexual and gender diversity to accompany these struggles. “I think this lets us see how more and more there is a conscious citizenry and part of that citizenship is LGTBIA that has been in the streets, that has fought despite the fact that this country and the whole world is deeply unfair to us,” she says.

“Despite the fact that this world has treated us in the worst way; we have been there to fight for equality, to fight for a democracy that has not finished recognizing our rights.”

Gahela urges that this fact must remain as part of the reflection and an analysis. “Because democracy was not only recovered by cis hetero people. It has also been recovered by women, and people in all their sexual and gender diversity,” she tells us. “Trans people whom this country does not allow even an ID with their name. They don’t even recognize our identity. We have also been the ones who have gone out to fight with courage and joy.”

She is referring to the fact that Peru does not have a Gender Identity Law which allows folks to change their names and gender identities on all their official documents. She thinks that it’s only a matter of time, but that one of the biggest obstacles is the financial barrier.

According to her, the changes of name and sex in official documents have to be given at the judicial level. That is, you have to sue the State so that the State, through a judicial process, recognizes that it has to change all your information.

“And that comes at a cost and it comes at a pretty high cost. Not only in economic and monetary terms, but also in emotional and psychological terms,” says Gahela. “Because nothing gives you assurance that this process will be satisfactory. You can end up with a transphobic judge who is going to say no, despite the expenses you have made, despite how difficult it is to have to go to court and support the change of your data.”

In Peru, citizens are struggling to have a mechanism that allows them to access data changes that are free, fast and secure. “The right to identity is not something that should be subject to your pocket, to the amount of coins you have in your pocket,” she says, “it should be subject only to who you are, right?”

CRIMINALIZATION OF PROTESTS

Why is the criminalization of protest so dangerous? In the days during the uprisings the right-leaning media in Peru have painted protesters negatively. Most recently, the media has portrayed farm workers who blocked off the roads in the North and South coast as “vandals,” for exercising their right to protest against agro-exploitation laws. In the last week, 70+ young people who attended the November protests have been arrested during a supposed “anti-terrorist” operative from the Ministry of Interior.

“I believe that the protests have succeeded in removing the usurper government, but the cost has been too high,” says Gahela. “We have seen dozens of young people injured, kidnapped, tortured, mistreated, killed like Inti, Bryan and Jorge.”

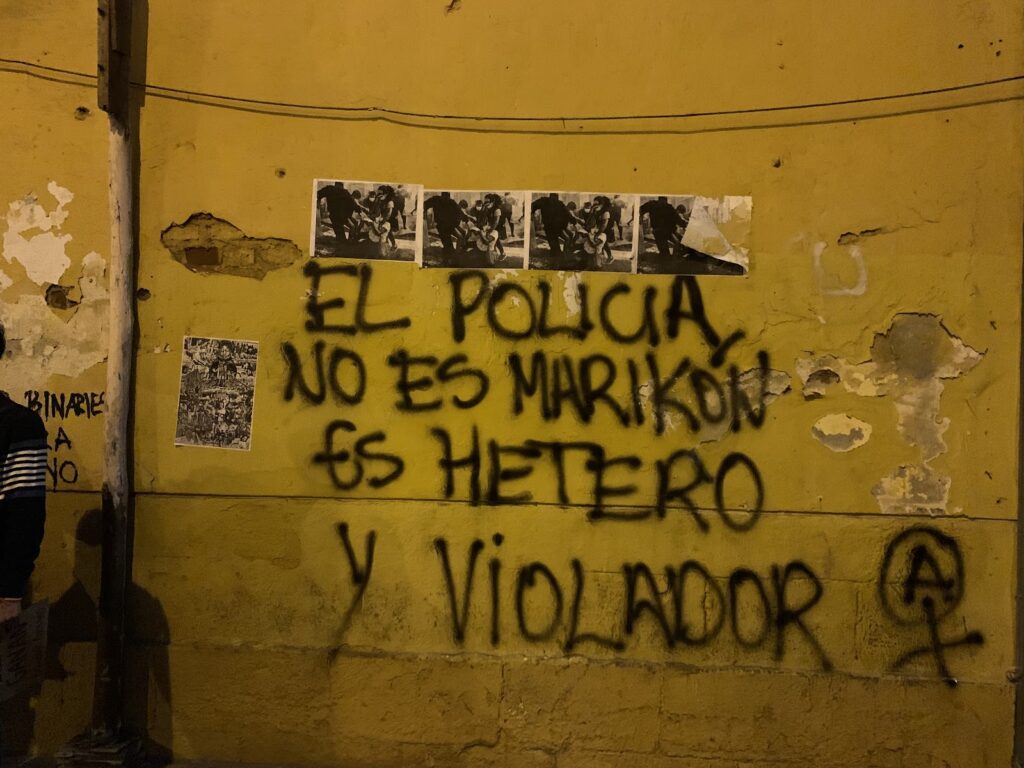

The criminalization of protest and police abuse is nothing new. In Peru, as in most nation-states, Gahela describes, the police is a repressive apparatus of the neoliberal system that has been murdering indigenous and Black folks for decades. An apparatus that has been raping women in patrol cars, murdering without mercy to impose extractive projects.

“We have seen it here in Bagua, when the Baguazo happened,” says Gahela referring to the massacre in Bagua in 2009, when 32 indigenous folks protesting against the FTA in Peru were murdered by police. “We have seen it in Tía María, in Espinar. We have seen it in different parts of the country.”

Gahela says we need to reflect, to get justice for the murders of Inti Sotelo Camargo (23), shot in the heart by police during a protest in Lima on November 14th, Jack Bryan Pintado (22), shot with over 10 bullets in the face and upper body by police on the same night as he deactivated tear gas bomb that had been shot at protesters, and Jorge Yener Muñoz (19), farm worker shot in the head by police just days ago while protesting for fair wages and the abolishing of agro-exploitation laws.

“We need to demand speedy justice,” says Gahela. “Because the justice that takes too long is not justice. We need to demand reparation for their families, for each of the people who were injured, kidnapped, mistreated, young people who came out to fight for their country, for their lives and for those of their peers.”

The police have historically violated those who have the least, shares Gahela, rural folks, street workers, informal workers, merchants who are on the streets. And yet the police never violate large commercial stores, big farmers or the owners of the big exploiting companies.

“Why do they violate those who have less?” asks Gahela. “This has to make us reflect.”

RAGE

“We have always been told that having anger or rage is wrong,” says Gahela sighing. She reflects on how we come from a history of struggle, of exploitation and persecution.

“Persecuted by the Church that today tells us what is right and what is wrong. What is sinning and what is not sin? Where is the blame?,” she says. “I am a very believing woman and I believe in goddesses, in the gods of love, of affection. I don’t believe in a God of guilt. That God does not represent me. That God doesn’t interest me.”

She shares how the people who lead the anti-rights and fundamentalist movements use the faith of the majority of the people to be able to spread their hate speech based on false arguments.

“We have the right to be angry,” says Gahela. “Don’t tell me not to be angry when one of my sisters is murdered, when I turn on the TV and see that they have murdered and dismembered, that they have burned one of our siblings.”

According to Gahela, despite the fact that they continually denounce this judicial system, it does not respond to their lives and does not allow them to achieve justice and reparation.

“Don’t tell me not to burn it all when I see how they rape and kill us,” she continues. “If tomorrow they rape or kill someone I love, I have every right to paint the streets, to fill them with graffiti, paint, and art. I have every right to tell the story through songs and murals, to unload my rage and my anger. Because unfortunately the mass media are not willing to touch what happens in the streets.”

REFLECTIONS

Gahela believes that Peruvians need to get rid not only of Vizcarra, of Merino, but also of all that political class that does not serve them. She, like many other Peruvians, believes that Peru needs a new constitution, seeing as the current one was written in 1993, and is part of the remains of the Fujimori dictatorship.

“This [current] Constitution is extractive, it is colonial, it is racist and it continues to see health, education as a service and not as a right,” she says.

She also sees it imperative to root our movements in intersectionality. Movements that include everyone. “I am not willing to give my life to a half revolution,” says Gahela. “I want a revolution that does not leave anyone out.”

Finally, Gahela left us with some offerings for all of us fighting across and beyond Abya Yala:

“I believe that at this moment we have the challenge of power. We have to look at each other, find each other, return to each other, embrace. Articulate and organize ourselves, because what we are experiencing is an attack. It’s an international onslaught. And the response from the dissident voices, from the ethnic and cultural diversity, from the people of Abya Yala has to also be in that collective sense. We have to recognize our diversity. We have to embrace our struggles and articulate our efforts. Because if the attack is continental, the answer has to be continental, the answer has to interweave all our voices and spaces.”

“So I think we have to keep organizing ourselves, we have to keep fighting, but above all we have to keep doing political pedagogy, pushing for changes, common meanings and the main thing I think is love. To love with madness, to love with passion, to love with abandon, right? And keep trusting, because even though it is difficult to trust, I think it is the most beautiful thing to be able to feel warm, to protect and to feel protected. The power to rediscover yourself in the eyes of another.”

[part of the series: RESISTENCIAS BEYOND BORDERS by Ebony Bailey and xime izquierdo ugaz in collaboration with Mijente]